Install Git Lfs For Mac

There are several ways to install Git on a Mac. The easiest is probably to install the Xcode Command Line Tools. On Mavericks (10.9) or above you can do this simply by trying to run git from the Terminal the very first time.

DM uses Git LFS to manage test datasets within our normal Git workflow.Git LFS is developed by GitHub, though DM uses its own backend storage infrastructure (see SQR-001: The Git LFS Architecture for background).

All DM repositories should use Git LFS to store binary data, such as FITS files, for CI.Examples of LFS-backed repositories are lsst/afw, lsst/hsc_ci, lsst/testdata_decam and lsst/testdata_cfht.

This page describes how to use Git LFS for DM development.

Installing Git LFS¶

Git LFS requires Git version 1.8.2 or later to be installed.

Download and install the git-lfs client by visiting the Git LFS homepage.If you downloaded the binary release, install git-lfs by running the provided install.sh.

Most package managers also provide the git-lfs client.Since, LFS is a rapidly evolving technology, package managers will help you keep up with new git-lfs releases.For example, Mac users with Homebrew can simply run brewinstallgit-lfs (and later update to a new version with brewupgradegit-lfs).

Once git-lfs is installed, run:

to configure Git to use Git LFS in your ~/.gitconfig file.

Next, decide whether you will need to push Git LFS data, or only clone and pull from Git LFS managed repositories.This affects how you set up authentication to DM’s Git LFS servers.The two configuration options are:

- Anonymous access for read-only LFS users.

- Authenticated access for read-write LFS users.

Option 1: Anonymous access for read-only LFS users¶

Follow these configuration instructions if you never intend to create a new Git LFS managed repository for DM, or push changes to LFS managed datasets.Skip to configuration Option 2 Zeppelin download icons for mac free. if this isn’t the case for you.

First, add these lines into your ~/.gitconfig file:

(This example includes the result of the earlier ‘lfs.batch false’ configuration command.)

Then add these lines into your ~/.git-credentials files (create one, if necessary):

That’s it.You’re ready to clone any of DM’s Git LFS managed repositories.

Option 2: Authenticated access for read-write LFS users¶

Follow these configuration instructions if you need to create or push changes to a DM Git LFS managed repository.Only GitHub users in the LSST GitHub organization can authenticate with DM’s storage service.If you only want read-only access to DM’s Git LFS managed repositories, return to Option 1.

First, add these lines into your ~/.gitconfig file:

(This example includes the result of the earlier ‘lfs.batch false’ configuration command.)

Then add these lines into your ~/.git-credentials files (create one, if necessary):

Next, set up a credential helper to manage your GitHub credentials (Git LFS won’t use your SSH keys).We describe how to set up a credential helper for your system in the Git set up guide.

Once a helper is set up, you can cache your credentials by cloning any of DM’s LFS-backed repositories.For example, run:

gitclone will ask you to authenticate with DM’s git-lfs server:

At the prompts, enter your GitHub username and password.

If you haveGitHub’s two-factor authentication enabled, use a personal access token instead of a password.You can set up a personal token at https://github.com/settings/tokens.

Once your credentials are cached, you won’t need to repeat this process on your system (unless you opted for the cache-based credential helper).

That’s it.Read the rest of this page to learn how to work with Git LFS repositories.

Using Git LFS-enabled repositories¶

Git LFS operates transparently to the user.Just use the repo as you normally would any other Git repo.All of the regular Git commands just work, whether you are working with LFS-managed files or not.

There are two caveats for working with LFS: HTTPS is always used, and Git LFS must be told to track new binary file types.

First, DM’s LFS implementation mandates the HTTPS transport protocol.Developers used to working with ssh-agent for passwordless GitHub interaction should use a Git credential helper, and follow the directions above for configuring their credentials.

Note this does not preclude using git+git or git+ssh for working with a Git remote itself; it is only the LFS traffic that always uses HTTPS.

Second, in an LFS-backed repository, you need to specify what files are stored by LFS rather than regular Git storage.You can run

to see what file types are being tracked by LFS in your repository.We describe how to track additional file types below.

Tracking new file types¶

Only file types that are specifically tracked are stored in Git LFS rather than the standard Git storage.

To see what file types are already being tracked in a repository:

To track a new file type (FITS files, for example):

Git LFS stores information about tracked types in the .gitattributes file.This file is part of the repo and tracked by Git itself.

You can gitadd, commit and do any other Git operations against these Git LFS-managed files.

To see what files are being managed by Git LFS, run:

Creating a new Git LFS-enabled repository¶

Configuring a new Git repository to store files with DM’s Git LFS is easy.First, initialize the current directory as a repository:

Make files called .lfsconfigand.gitconfigwithin the repository, and write these lines into both:

Note that older versions of Git LFS used .gitconfig rather than .lfsconfig.As of Git LFS version 1.1 .gitconfig has been deprecated, but support will not be dropped until LFS version 2.New repositories should still use both configuration files since DM’s Jenkins server still uses a pre-1.1 git-lfs client.

Next, track some files types.For example, to have FITS and *.gz files tracked by Git LFS, Best pdf annotation app for mac and ipad reddit.

Add and commit the .lfsconfig, .gitconfig, and .gitattributes files to your repository.

You can then push the repo up to github with

We also recommend that you include a link to this documentation page in your README to help those who aren’t familiar with DM’s Git LFS.

In the repository’s README, we recommend that you include this section:

Introduction

Part 1 - The Basics

What is Version Control?

Why Use Version Control?

Getting Ready

The Basic Workflow

Starting with an Unversioned Project

Starting with an Existing Project

Working on Your Project

Part 2 - Branching & Merging

Branching can Change Your Life

Working With Branches

Saving Changes Temporarily

Checking Out a Local Branch

Merging Changes

Branching Workflows

Part 3 - Sharing Work via Remote Repositories

Introduction to Remote Repositories

Connecting a Remote Repository

Inspecting Remote Data

Integrating Remote Changes

Publishing a Local Branch

Deleting Branches

Part 4 - Advanced Topics

Undoing Things

Inspecting Changes with Diffs

Dealing With Merge Conflicts

Rebase as an Alternative to Merge

Submodules

Workflows with git-flow

Handling Large Files with LFS

Authentication with SSH Public Keys

Part 5 - Tools & Services

Desktop GUIs

Diff & Merge Tools

Code Hosting Services

More Learning Resources

Appendix

Version Control Best Practices

Command Line 101

Switching from Subversion to Git

Why Git?

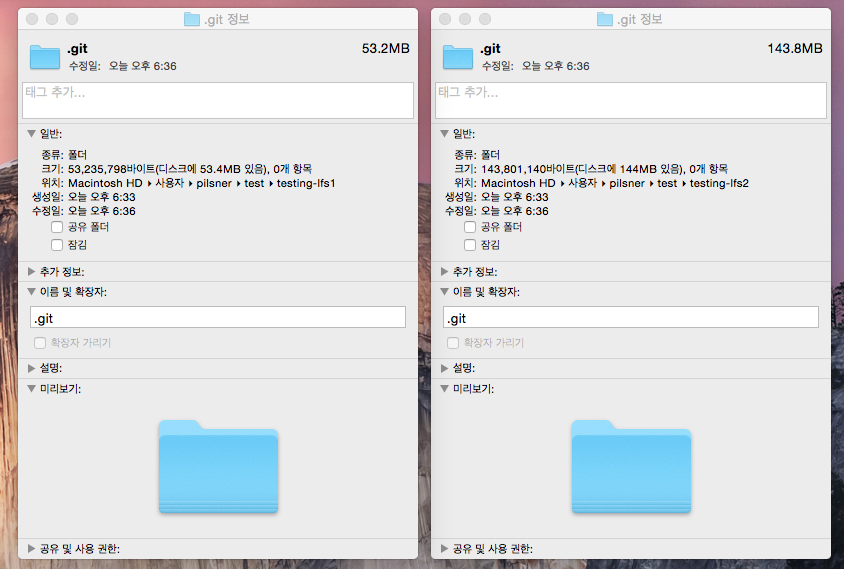

Working with large binary files can be quite a hassle: they bloat your local repository and leave you with Gigabytes of data on your machine. Most annoyingly, the majority of this huge amount of data is probably useless for you: most of the time, you don't need each and every version of a file on your disk.

This problem in mind, Git's standard feature set was enhanced with the 'Large File Storage' extension - in short: 'Git LFS'. An LFS-enhanced local Git repository will be significantly smaller in size because it breaks one basic rule of Git in an elegant way: it does not keep all of the project's data in your local repository.

Let's look at how this works.

Only the Data You Need

Let's say you have a 100 MB Photoshop file in your project. When you make a change to this file (no matter how tiny it might be), committing this modification will save the complete file (huge as it is) in your repository. After a couple of iterations, your local repository will quickly weigh tons of Megabytes and soon Gigabytes.

When a coworker clones that repository to her local machine, she will need to download a huge amount of data. And, as already mentioned, most of this data will be of little value: usually, old versions of files aren't used on a daily basis - but they still weigh a lot of Megabytes..

The LFS extension uses a simple technique to avoid your local Git repository from exploding like that: it does not keep all versions of a file on your machine. Instead, it only provides the files you actually need in your checked out revision. If you switch branches, it will automatically check if you need a specific version of such a big file and get it for you - on demand.

Pointers Instead of Real Data

But what exactly is stored in your local repository? We already heard that, in terms of actual files, only those items are present that are actually needed in the currently checked out revision. But what about the other versions of an LFS-managed file?

To do its size-reducing wonders, LFS only stores pointers to these files in the repository. These pointers are just references to the actual files which are stored elsewhere, in a special LFS store.

An Additional Object Store

The usual Git setup is probably old hat to you:

- Your local computer is home to a local Git repository and the project's Working Copy.

- Most likely (although not mandatory) there's also a remote server involved which hosts the remote repository.

With LFS, this classic setup is extended by an LFS cache and an LFS store:

- Remember that an LFS-tracked file is only saved as a pointer in the repository. The actual file data, therefore, has to be located somewhere else: in the LFS cache that now accompanies your local Git repository.

- On the remote side of things, an LFS store saves and delivers all of those large files on demand.

Whenever Git in your local repository encounters an LFS-managed file, it will only find a pointer - not the file's actual data. It will then ask the local LFS Cache to deliver it. The LFS Cache tries to look up the file by its pointer; if it doesn't have it already, it requests it from the remote LFS Store.

That way, you only have the file data on disk that is necessary for you at the moment. Everything else will be downloaded on demand.

Before we get our hands dirty installing and actually using LFS there's one last thing to do: please check if your code hosting service of choice supports LFS. Although most popular services like GitHub, GitLab, and Visual Studio already offer support for LFS, it's nothing to take for granted.

Installing Git LFS

LFS is a fairly recent invention and not (yet) part of the core Git feature set. It's provided as an extension that you'll have to install once on your local machine.

Installation is quick and simple:

- Linux: Debian and RPM packages are available from PackageCloud.

- macOS: You can either use Homebrew via 'brew install git-lfs' or MacPorts via 'port install git-lfs'.

- Windows: Use the Chocolatey package manager via 'choco install git-lfs'.

To finish the installation, you need to run the 'install' command once to complete the initialization:

Concept

Good news if you're using the Tower desktop GUI: all recent versions of the app already include LFS. You don't have to install anything else!

Tracking a File with LFS

Out of the box, LFS doesn't do anything with your files: you have to explicitly tell it which files it should track!

Let's start by adding a large file to the repository, e.g. a nice 100 MB Photoshop file:

With the 'track' command, you can tell LFS to take care of the file:

If you expected fireworks to go off, you'll probably be a bit disappointed: the command didn't do much. But you'll notice that the '.gitattributes' file in the root of your project was changed! This is where Git LFS remembers which files it should track.

If we look at it now, we'll be happy to see that LFS made an entry about our 'design.psd' file:

Just like the '.gitignore' file (responsible for ignoring items), the '.gitattributes' file and any changes that happen to it should be included in version control. Put simply, you should commit changes to '.gitattributes' to the repository like any other changes, too:

Tracking Patterns

It would be a bit tedious if you had to manually tell LFS about every single file you want to track. That's why you can feed it a file pattern instead of the path of a particular file. As an example, let's tell LFS to track all '.mov' files in our repository:

To avoid some slippery slopes, keep two things in mind when creating a new tracking rule:

- Don't forget the quotes around the file pattern. It indeed makes a difference if you write git lfs track '*.mov' or git lfs track *.mov. In the latter case, the command line will expand the wildcard and create individual rules for all .mov files in your project - which you probably do not want!

- Always execute the 'track' command from the root of your project. The reason for this advice is that patterns are relative to the folder in which you ran the command. Keep things simple and always use it from the repository's root folder.

Which Files Are We Tracking?

At some point, you might want to check which files in your project you are effectively tracking via Git LFS. This is where the 'ls-files' command comes in handy: it lists all of the files that are tracked by LFS in the current working copy.

Whenever you're in doubt if a certain file is really managed by LFS, simply assure yourself with the 'ls-files' command.

When to Track

You can accuse Git of many things - but definitely not of forgetfulness: things that you've committed to the repository are there to stay. It's very hard to get things out of a project's commit history (and that's a good thing).

In the end, this means one thing: make sure to set your LFS tracking patterns as early as possible - ideally right after initializing a new repository. To change a file that was committed the usual way into an LFS-managed object, you would have to manipulate and rewrite your project's history. And you certainly want to avoid this.

Cloning a Git LFS Repository

To clone an existing LFS repository from a remote server, you can simply use the standard 'git clone' command that you already know. After downloading the repository, Git will check out the default branch and then hand over to LFS: if there are any LFS-managed files in the current revision, they'll be automatically downloaded for you.

That's all well and good - but if you want to speed up the cloning process, you can also use the 'git lfs clone' command instead. The main difference is that, after the initial checkout was performed, the requested LFS items are downloaded in parallel (instead of one after the other). This could be a nice time saver for repositories with lots of LFS-tracked files.

Working with Your Repository

Undeniably, the best part about Git LFS is that it doesn't require you to change your workflow. Apart from telling LFS which files it should track, there is nothing to watch out for! No matter if it's committing, pushing or pulling: you can continue to work with the commands you already know and use.